Polymarket Volume Is Being Double-Counted

12.08.2025|Storm Slivkoff

After analyzing Polymarket’s market structure, event data, and smart contracts, we discovered that most Polymarket analyses and dashboards have been mistakenly double-counting volume. Polymarket’s onchain data is quite complex, and this has led to widespread adoption of flawed accounting methods. However, this data becomes easy to work with using the principles explained below.

This article contains the following sections:

1. Anatomy of a Polymarket Trade

How do Polymarket trades manifest in onchain data?

2. Not All Matches Are Swaps

How do prediction market matching engines work?

3. Prediction Market Volume Metrics

What is the right way to measure volume?

Main Claims:

- The common approach of summing Polymarket’s OrderFilled events leads to double counting volume. This approach double counts both the number of contracts traded and USD cash flow. For example, a simple sale of YES tokens for $4.13 gets recorded as $8.26 worth of volume. This is because there are separate OrderFilled events representing the maker side and taker side of the trade.

- Volume on prediction markets should be measured using a one-sided volume metric, such as taker-side volume or maker-side volume. There are multiple valid ways to measure prediction market volume, but summing up all OrderFilled events is not one of them.

This article is unrelated to wash trading or other types of volume classification. We are simply describing how to measure the total raw volume occurring on Polymarket, especially in a manner that enables apples-to-apples comparisons to other prediction market platforms.

Anatomy of a Polymarket Trade

We will begin by describing the onchain data associated with each Polymarket trade.

Polymarket trade transactions all follow a rigid template:

- There is at most one group of matched Polymarket orders per Polygon transaction.

- Each set of matched orders has exactly one taker and at least one maker.

- Trade transactions are submitted by ~50 Polymarket-affiliated EOA’s.

Event Structure

Polymarket uses 2 EVM events to track trades: OrderFilled and OrdersMatched.

Both events have these fields:

- makerAssetID: either 0 (for USDC), or the YES token id, or the NO token id

- takerAssetID: either 0 (for USDC), or the YES token id, or the NO token id

- makerAmountFilled: amount of maker tokens

- takerAmountFilled: amount of taker tokens

The OrderFilled event also has a maker field and taker field that we describe below.

Event Sequence

Each Polymarket trade transaction has the same sequence of events:

- There is at least one “maker-focused” OrderFilled event

- one of these events is emitted for each maker involved in the transaction

- the maker values of these events are usually (but not always) distinct

- all of these events have the same taker, which is the overall taker of transaction

- neither the maker nor taker of these events are Polymarket exchange contracts

- Then there is exactly one “taker-focused” OrderFilled event

- its maker is the transaction’s overall taker

- its taker is a Polymarket exchange contract (CTF or NegRisk)

- Finally there is exactly one OrdersMatched event

- it has the same makerAmountFilled and takerAmountFilled as the “taker-focused” OrderFilled event of (2)

Critically, item (2) is redundant with item (1). This final OrderFilled is a second representation of the same trades, rather than an additional trade between the taker and Polymarket exchange. It does not represent additional economic activity, nor does it represent any additional transfer of risk between market participants.

Furthermore, a common point of confusion is that the total token volume recorded by OrderFilled events is roughly 2x the total token volume recorded by OrdersMatched events. This discrepancy is resolved by realizing that each transaction contains two sets of OrderFilled events that both represent the same trades.

An additional point of confusion is that these two sets of OrderFilled events, corresponding to makers and takers, can measure different amounts of volume for an individual trade. This is resolved by realizing that makers and takers can experience different amounts of volume during split trades and merge trades. But aggregated over many trades, on the timescales of days or months, the amount of maker volume and taker volume tend to converge to the same value. We elaborate on this in a later section.

Smart Contract Structure

Polymarket’s event sequence is further clarified by looking at the Polymarket exchange contracts. Each trade is facilitated by one of two exchange contracts, CTF or NegRisk CTF. The portion of code that emits OrderFilled and OrdersMatched is shown in Figure 1. This code is the same in both contracts.

Figure 1: Event-emitting portion of Polymarket exchange smart contracts. The number labels correspond to the items in the “Event sequence” section above.

Each Polymarket trade follows the same sequence:

- Enter the contract via the matchOrders() function, which simply calls _matchOrders()

- Transfer taker’s tokens from the taker to the exchange contract

- _fillMakerOrders() loops through the makers. For each one:

- Compute fees to the maker

- Perform split/merge operations if necessary (see next section)

- Transfer maker tokens from the maker to the exchange contract

- Transfer taker tokens from the exchange contract to the maker

- Transfer maker fees from exchange contract to fee collector

- Emit an OrderFilled event describing the portion of the taker’s trade filled by the maker

- Transfer makers’ tokens from the exchange contract to taker

- Transfer taker fees from the exchange contract to fee collector

- Emit an OrderFilled event describing the entire set of fills

- Emit an OrdersMatched event describing the entire set of fills

In this design the exchange contract acts as a router. It is either the sender or receiver of each token transfer. Critically though, the exchange takes no positions, it provides no funds, it assumes no risk, and it is not the counterparty to any trade. The only trades that occur are between the taker and each of the makers. Thus, the two types of OrderFilled events are two representations of the same trades and they should not be added together.

It should be noted that none of the OrderFilled events contain incorrect information. There are many reasons why a smart contract might be designed to emit extra events (e.g. it might make it easier to report each user’s history on the frontend). Incorrect information only enters the picture when someone attempts to compute volume by summing up all of the OrderFilled events.

Not All Matches Are Swaps

Beyond the redundant OrderFilled emission, Polymarket transactions can also be confusing because the matching engine can match orders across the YES and NO orderbooks within the same multileg trade. These are not conventional swaps, and at first glance they can appear to produce accounting that seems arbitrary or imbalanced.

Take this Polymarket trade for example, with Polygonscan representation shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Example of a “confusing” Polymarket trade

Polygonscan summarizes this transaction as “Place Bet of $28.41”. It was an active market that had not yet resolved. So why is there a party that nets out $6780?

What actually happened here:

- The taker 0x0c45 sold $90 of YES shares in a market order

- This taker order was filled by matching with two market makers

- The first market maker 0xd9A5 bought $28 of YES

- The second market maker 0x8E8C sold $6780 of NO

To understand the last bullet, it is necessary to understand the YES-NO Split-Merges

YES-NO Split-Merges

Polymarket represents positions using the dual assets of YES tokens and NO tokens. In the main smart contract controlling these tokens, the only way to interconvert between these YES and NO are split and merge operations:

- Split: Exchange $1 for (1 YES token + 1 NO token)

- Merge: Exchange (1 YES token + 1 NO token) for $1

Prior to the transaction above, second market maker 0x8E8C had opened sell orders for their NO tokens. The matching engine figured out that some of the YES tokens being sold by taker 0x0c45 could be merged with some of the NO tokens being sold by maker 0x8E8C, which would produce sufficient USDC to partially fill both orders. Then to execute the trade, the exchange contract 1) gathers the YES and NO tokens from both parties, 2) merges them, and 3) then distributes the proceeds pro rata according to the trade’s execution price.

Token Accounting

Here is the sequence of token transfers in the transaction (Figure 3A), along with the associated net balance changes (Figure 3B).

The exchange is the sender or receiver of each of these transfers. The vault is the “Conditional Tokens” contract that stores all of the USDC backing the YES-NO token pairs.

Figure 3a: Token transfers associated with the “confusing” transaction

Figure 3b: Balance changes associated with the “confusing” transaction

Market Structure of Splits and Merges Versus Swaps

The market structure can be described as follows: Polymarket’s matching engine matches makers and takers. Some of these matches are conventional swaps, where one market participant transfers their risk exposure to another market participant in exchange for USDC. This works similarly to spot exchanges like Uniswap or Binance. But the YES-NO structure of prediction markets also allows another type of match using a split or merge. In these special matches:

- The maker and taker are either both sending or both receiving USDC (instead of there being one sender and one receiver).

- The buyer and seller mutually agree to take opposite sides of a market, either to create new open interest or to close existing open interest. The open interest in the system increases or decreases (instead of remaining constant as in a spot swap).

- The maker and taker are usually sending or receiving different amounts of value (instead of the buyer’s USD delta being approximately the same size to the seller’s USD delta).

Split trades are matches where maker and taker agree to both exchange their USDC for shares, and then one party receives the YES exposure and the other receives the NO exposure. Merge trades are matches where maker and taker agree to exchange their opposing YES and NO shares for USDC.

With these principles in mind we can describe the example trade from above in more precise terms. It was a two-leg trade, where the first leg was a swap, and the second leg was a merge.

- In the swap leg, the taker exchanged 3,157.02 YES tokens for $28.41, and the maker exchanged $28.41 for 3,157.02 YES tokens. Both maker and taker experienced the same amount of cash flow volume, $28.41. They also experienced the same amount of contract volume, 3,157.02.

- In the merge leg, the taker exchanged their 6,842.98 YES tokens for $61.59, and the maker exchanged 6,842.98 NO tokens for $6781.39. The taker and maker experienced the same amount of contract volume 6,842.98, but different amounts of cash flow volume.

- Summing the OrderFilled event report simply adds the maker volume to the taker volume, as there are separate OrderFilled events representing the maker side and taker side of the trade.

- It reports a total contract volume of 3,157.02 + 3,157.02 + 6,842.98 + 6,842.98 = 20,000

- It reports a total USDC volume of 28.41 + 28.41 + 61.59 + 6781.39 = $6899.80

As explained in the next section, there are multiple valid ways to interpret how much volume occurred in the second leg of the trade, but adding up maker and taker is not one of them. This sum is a form of double counting that produces a volume number that is not comparable to volume metrics of other prediction market trading venues.

Prediction Market Volume Metrics

There are multiple valid ways to compute volume on prediction markets. However, all of these approaches roughly agree on a volume value around 50% of the Polymarket’s OrderFilled sum.

For a complete accounting, we will start with the 8 types of simple trades that occur on Polymarket:

- Taker buys YES, maker sells YES (swap)

- Taker buys NO, maker sells NO (swap)

- Taker sells YES, maker buys YES (swap)

- Taker sells NO, maker buys NO (swap)

- Taker buys YES, maker buys NO (split)

- Taker sells NO, maker sells YES (merge)

- Taker sells NO, maker sells YES (merge)

- Taker sells YES, maker sells NO (merge)

We built a simulator that illustrates how various trading metrics behave under each of these 8 trade types. For each trade type, the simulator computes 1) maker/taker balance changes, 2) open interest change, and 3) a variety of volume metrics. An example output is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Polymarket volume simulator spreadsheet

The only two inputs needed for the simulation are 1) the YES price and 2) the number of contracts traded. You can make a copy of the spreadsheet and change these parameters to perform your own simulations. For simplicity, we assume zero fees and (NO price) equals exactly $1 - (YES price).

We will now go through each item in the simulator output.

Account Deltas and Open Interest Changes

The first few columns in the simulator track how much the open interest and maker/taker balances change during each trade.

Take note of a few invariants:

- For each trade type, the taker and maker always take opposite positions. One is long YES resolution, and the other is short YES resolution.

- The taker and maker YES and NO deltas always have the same absolute value. This is different from their USDC deltas, which can have different absolute values.

- Split trades always increase open interest, merge trades always decrease open interest, and swap trades always leave open interest unchanged.

Volume Metrics

There are two categories of prediction market volume metrics in common use:

- Notional Volume: number of contracts traded

- Cash Flow Volume: the amount of USD exchanged at time of trade

Computing these metrics for swap trades is straightforward. The notional volume is simply the number of contracts traded. The cash flow volume is the number of contracts traded multiplied by the share price. For both of these volume metrics, Polymarket’s OrderFilled sum gives a value that is 2x the correct value.

Computing these metrics for split trades and merge trades is more complicated because they are not swaps in the conventional sense (see the Splits and merges versus swaps section). In a conventional swap, the maker and taker experience the same amount of volume. But in a split trade or merge trade, the maker and the taker can experience different amounts of volume. We are not opinionated about whether to measure the maker’s volume, the taker’s volume, or something in between. However, simply adding the two together is double counting, just as it would be with a swap trade.

With these considerations in mind, computing the notional volume for split trades and merge trades becomes straightforward. It is simply the number of contracts that are split or merged.

Computing the cash flow volume for split trades and merge trades is the most complicated case. As mentioned above, the maker and taker will experience different amounts of cash flow. Whether to focus on the maker’s cash flow, the taker’s cash flow, the maker taker mean, or some other approximation (like share-priced volume) can depend on the context. These metrics can each produce different volume values for an individual trade. However, these metrics all produce about the same volume numbers when aggregated over longer timescales of days or months (see Figure 5 below). Thus, the exact choice of cash flow metric is often unimportant. The only important note is that summing up OrderFlow events does not agree with these volume metrics, and it instead produces a value about 2x as large due to double counting (see Figure 5 below).

Polymarket USDC Volume Metrics

Figure 5: Monthly Polymarket volume under different metrics. The Taker-side volume, Maker-side volume, and share-priced volume are each around half of the OrderFilled sum. One indicator that a Polymarket volume chart might be using OrderFilled sums is checking whether monthly volume for 2024-10 and 2024-11 is around $2.5B.

Realworld Examples

The final columns of the spreadsheet provide 4 examples of historical transactions for each of the 8 trade types. The price and size parameters of each example can be input into cells A1 and A2 of the spreadsheet to simulate the sum of each transaction’s OrderFilled events.

Figure 6: The spreadsheet contains 4 examples of realworld trades for each of the 8 trade types

A view of these examples is shown in Figure 6. Note also that these examples are drawn from both the Polymarket CTF Exchange and the Polymarket Negrisk exchange, and each exchange has identical OrderFilled emissions.

One of the difficulties of analyzing Polymarket data has been the large number of trade types. Even with knowledge of the 8 trade types, it is not easy to find or identify specific trade types using a block explorer. These 32 example trades should be a useful resource for anyone trying to learn more about Polymarket data.

Which Metrics To Use?

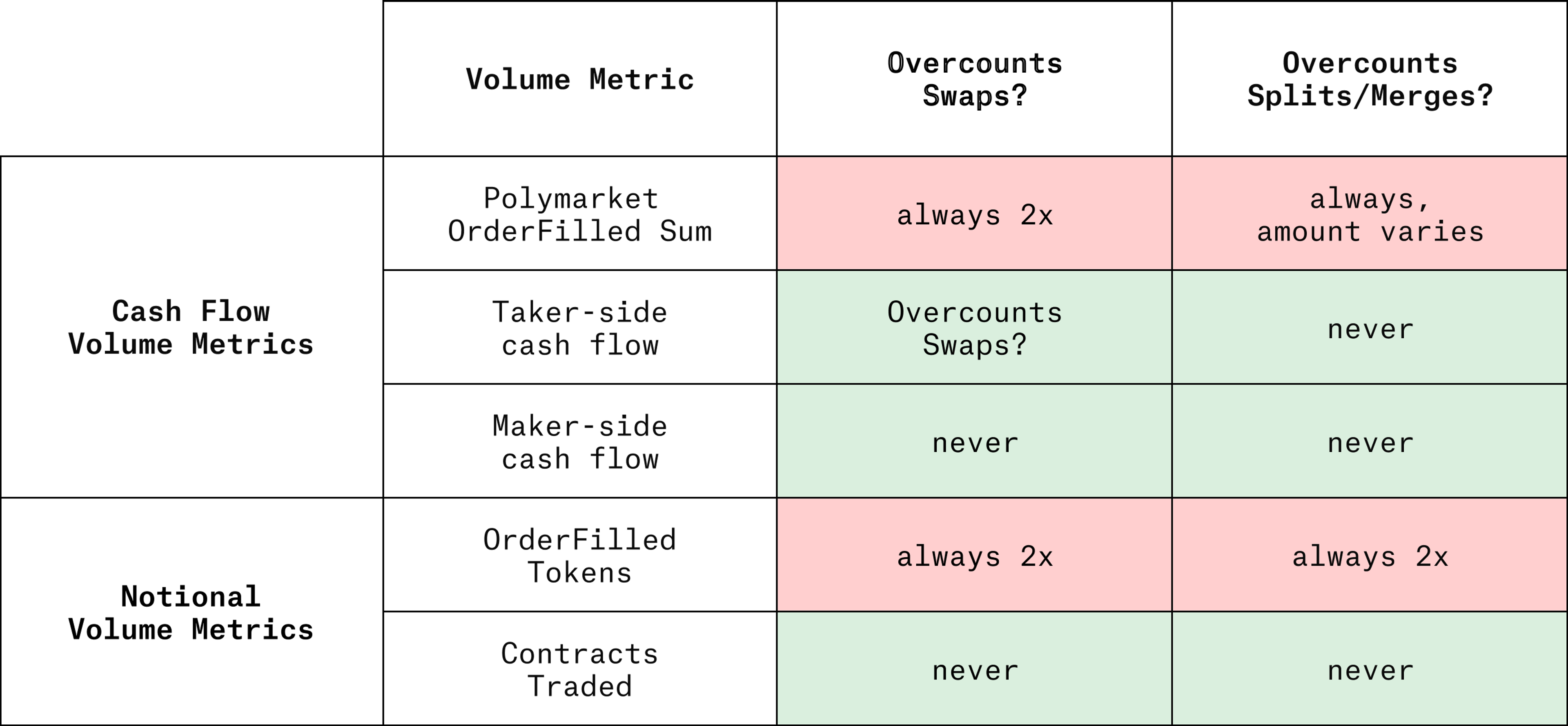

Here is a comparison of the metrics mentioned in a single view:

Figure 7: Comparison of prediction market volume metrics

For notional volume, measurement is straightforward. Simply measure the number of contracts traded.

For cash flow volume there are multiple possibilities. Can use the cash flow of the maker, or the cash flow of the taker, or an average of the two. Each of these can be derived from Polymarket’s onchain data, and each produces similar volume numbers when aggregated over days or months (Figure 5).

Taker-side volume can be obtained by filtering and summing OrderFilled events where the taker field is equal to one of the two exchange contracts (CTF 0x4bfb41d5b3570defd03c39a9a4d8de6bd8b8982e and NegRisk 0xc5d563a36ae78145c45a50134d48a1215220f80a). Maker-side volume can be computed by filtering and summing OrderFilled events where the taker field is not equal to either of these exchange contracts.

Conclusion

Prediction markets are rapidly evolving into a critical financial sector. As the category matures, the industry should converge on consistent, transparent, and objective reporting standards. This is particularly important for comparing activity across platforms, as well as assessing the growing role of prediction markets in everyday life.

In our investigation into this topic, we discovered that most Polymarket analyses and dashboards have been unintentionally double-counting volume. The confusion results from interacting layers of complexity:

- Swap matches and split/merge matches lead to 8 possible types of single-leg trades, and an even larger variety of multi-leg trades.

- Each type of trade leads to slightly different event emissions from Polymarket contracts.

- Although no single Polymarket event contains incorrect information, the event stream contains redundant representations of the maker side and taker side of each trade. Simple summation of these events leads to double counting.

These factors are mostly undocumented, and standard tools like block explorers are not sufficient for untangling the complexity. A more precise account of this data only emerges when examining multiple lines of evidence (market structure, event emissions, and smart contract architecture). But taken together, these lines of evidence paint a clear and consistent view of how prediction market trades can be measured and compared.

Massive thanks to dash, Allium, Dan Smith, Chaos Labs, Ricardo de Arruda, Ciamac Moallemi, Dan Robinson, and frankie for feedback + conversations that helped untangle this data

Disclosure: Paradigm is an investor in Kalshi, a competitor to Polymarket.

Appendix: Examples in the Wild

Compare the charts below to Figure 5. Note that a value of ~$2.5B monthly volume in the months of 2024-10 and 2025-11 generally indicates that a dashboard is computing volume by summing up all OrderFilled events.

We have validated this information with multiple dashboard creators and data analysts. DefiLlama, Allium, Blockworks, and others are now updating their dashboards to remove the double-counting.

Copyright © 2026 Paradigm Operations LP All rights reserved. “Paradigm” is a trademark, and the triangular mobius symbol is a registered trademark of Paradigm Operations LP